articles/Lighting/fillinflash-page1

Fill In Flash - part 1 of 1 2

by Tom Lee Published 01/08/2004

Spurred on by our Chairman of Qualifications Terry Hansen, we take a look at the options available for fill-in flash or synchro-sunlight. Terry has, for some time, been striving to get the message across that poor use of or complete lack of fill flash is causing a fall in standards of some applicant's work. This has been exacerbated by the move first to 35mm SLRs and now to digital. Both suffer from a slow synchronisation speed, limiting the options for fill flash. However we will show in this first article what technology is actually available and follow it up later on the practical use of these technologies in the wedding market.

Acommon theme for failure of qualification applications is the lack of lighting control. This can take the form of too much flash, too little flash or not using it at all when you should be. If you think that its use is obvious or you routinely use it, this article is not for you, but judging by some of the panels we are asked to adjudicate upon, an article will not be wasted. One of the problems of the manuals of flashguns is that they are larger than those for your camera and so it is worthwhile to shine some light into these dark places!

Basics

Fill in Flash of synchro-sunlight is the use of additional (flash) lighting to supplement or enhance the existing ambient light.The ambient is the sun for synchro sunlight but could be the existing tungsten or bounced flash for fill in flash.There are a number of possible effects that additional flash light may produce in an image, including:

1. It places a catch light in the eyes of the subject(s). 2. It fills in the deep eye sockets under strongly overhead lighting (including bounced flash).

3. It adds overall sparkle to the shot.

4. It can be used to balance the interior and exterior light levels.

5. It can be used to reduce the contrast ratio of strongly lit subjects (including back lit subjects).

There can also be a number of negative effects

1. Too much light, even if it is at the correct level for subjects close to the camera, can create total black out of the background if it is some distance away.

2. A gun too close to the lens axis can cause red eye.

3. If the light from a supplementary flashgun is too strong it can cast its own ugly shadow around the rim of the subject(s) or onto a background some distance away (e.g. on the stairs at a reception).

4. Turning the camera to vertical (portrait) mode with an attached flash can move the flash to a less favourable position (on the side) or an unacceptable position (underneath) in relation to the camera.

5. Flash light catching on a reflective surface (eg mirror, vehicle or spectacles) can cause very distracting highlights or can fool an automatic exposure system. Control is everything If letting the camera work on P Mode is dangerous, putting an automatic flash on top of it only multiplies the problem. In the worst case it takes over control of the camera, delivering an average effect rather than the desired one. At best it can actually be very good as long as the user is aware of subject failure and makes adjustments accordingly. Spurred on by our Chairman of Qualifications Terry Hansen, we take a look at the options available for fill-in flash or synchro-sunlight. Terry has, for some time, been striving to get the message across that poor use of or complete lack of fill flash is causing a fall in standards of some applicant's work. This has been exacerbated by the move first to 35mm SLRs and now to digital. Both suffer from a slow synchronisation speed, limiting the options for fill flash. However we will show in this first article what technology is actually available and follow it up later on the practical use of these technologies in the wedding market.

The light delivered by a flash depends only upon the size of the capacitor that discharges into the flash tube and the optics of the reflector. This is why most top of the camera flashguns have roughly the same guide number - they are physically the same size and that governs the capacitor size. Basically, bigger flashes need bigger batteries and more flashes need more batteries. The strength of the pentaprism mount and the balance of a camera limits most camera top flashes to 4 AA size batteries and a capacitor which delivers a Guide Number of about 30.The capacity of the batteries limits the number of flashes to something like a 35mm film's worth although this has improved with NiMH batteries of 2400mAh capacity. If you need more than that you have to provide power from a waist pack or take the flash off the pentaprism and store larger batteries in the stem of a hammer head gun such as the Metz featured in this article. Moving the power pack to the waist opens a number of possibilities including faster recycle times (sometimes by taking high voltage current up directly to the head) and more flashes .

How Much Flash?

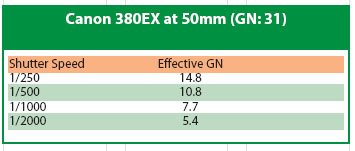

In order to understand the nature of flash balancing you first have to understand the way it works. The duration of a flash is short - typically between 1/300th and 1/1000th of a second, faster at the lower powers and rising to as high as 1/20,000th at very low power settings of a large gun. Providing that the shutter is open long enough, the flash light reaching the film or digital detector is governed solely by the lens aperture - the f stop. On a focal plane shutter, the blinds must be fully open when the flash goes off or they will obscure part of the detector. Typically this limits the flash synchronisation speed to a maximum of around 1/250th of a second but it can be as low as 1/60th.The shutter blades are now moving at close to mach 1 and so even faster synch speeds are hard to achieve although the new Nikon D70 synchs at 1/500ths.

The rules for flash are thus quite simple

1. Flash intensity at the film detector is governed by aperture of the lens

2. Exposure intensity from ambient light is governed by the aperture and the shutter speed.

3. The shutter speed has to be at or slower than the synchronisation speed.

How Much Light?

The old-fashioned "one over the ASA" rule still holds even though the methods of rating film speeds are a little different is the ISO system. Basically there are 5 specified lighting levels specified

If you take the reciprocal of the ASA (or ISO) speed and use that as your shutter speed, the 5 conditions require apertures of f16, f11, f8, f5.6 and f4 respectively. That is, a 125 ISO film would need 1/125th of a second at f11 to expose a garden scene in bright sunlight. It is therefore possible to sit down and work out the effect of flash and fill flash from the comfort of your studio before you set off to the event.Suppose you are using Fuji NPS 160 rated at 160 ISO. This would call for a base exposure of 1/160ths at f11 for a bride in sunlight. Now assume that you have a flash unit with a Guide Number of 45 (in metres at 160 ISO). If you assume that your subject is 3 metres away from the flash head then the aperture for correct flash exposure will be 45/3 = f17 (f16 for cash!).

Given that we have to remain at 1/160th to synchronise the flash, our aperture for 160 ISO Fuji NPS is f11 - that is a stop less and the flash is a whole stop too strong for flash only exposure.

Unless you are in blinding back lit sunshine, we really want our fill flash to contribute more like ¼ of the total light and so you can track down the table below to arrive at the correct fraction of flash power needed.

You are currently on page 1 Contact Tom Lee

1st Published 01/08/2004

last update 09/12/2022 14:54:13

More Lighting Articles

There are 0 days to get ready for The Society of Photographers Convention and Trade Show at The Novotel London West, Hammersmith ...

which starts on Wednesday 15th January 2025