articles/Profiles/mayhem-page2

From Mayhem To Mamiyaa - part 2 of 1 2 3

Published 01/12/1999

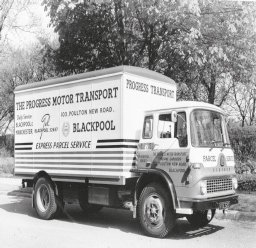

These were what pressmen used in those days. The 'amateur snapshot camera' which Franke & Heidecke produced eventually became the outstanding professional tool of the epoch and only lost its position through lack of foresight and research and development. Had things been otherwise, today's Hasselblad might never have been. It was not until the Korean war, which brought the western press photographers into contact with the Nikon and Canon range finder cameras from the east that the complacency of the house of Rollei was shattered and developments began which led to photography being what it is today - developments which I see myself as living through from the beginning. As soon as I was demobbed I joined Blackpool Amateur Photographic Society and enrolled for 'night school' at Blackpool Technical College. Studies in those days took a long time (mine took eighteen years): during the day there was living to be earned in the harsh world of post war Britain where there was no place for an inexperienced student in the then ver y limited world of professional photography. When I came home from the war I got a my first job as a driver with Blackpool Council. I had spent most of the war as a driver, and had made it my business to drive everything I could get my hands on, from Sherman tanks to German motor bike and sidecar combinations - BMWs with both forward and reverse gears and so fell easily into the work. I must surely have been the only council lorry driver with a cab full of photography text books! My job was driving - others loaded and unloaded, so there were precious moments when I could pursue my studies and keep up the dream which I had cherished ever since Brunswick. I read every photographic book I could get my hands on and studied every aspect of photography as hard as I could and in every spare moment.

In my spare time I also did portraiture and wedding work and specialised in child photography. Apart from weddings, most of this work was done by visiting the homes of my subjects, and using quarter plate 'Soho' or 'Thornton Packard' and 6 x 6 cm Rolleiflex.

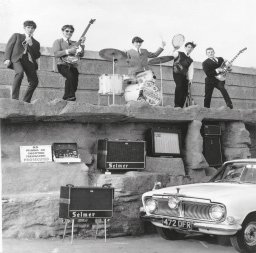

Lighting was tungsten. I learned how to retouch negatives (very few people could do this in those days) and besides making a start on getting my name known, the work was valuable experience and stood me in good stead when it came to exams and to getting work full time in photography. In addition to portraits and groups, my albums from this period contain photographs taken on stage, using stage lighting, and of events and entertainers on the time. All these were processed and printed in my home darkroom. There were no professional laboratories in those days - we had to do everything ourselves, and know how to do it properly if we were to survive. In 1962 I passed my City and Guilds final and felt that I could seek a job in photography. My first job was with English Electric (later BAC, now BAE). Here my work was mostly in the darkroom and was associated with the technical recording of the testing carried on on prototypes of the 'P1' - later to become known as the 'Lightning' fighter bomber. We were the black box of the day. A kind of photographic paper was used to record a trace of instrument readings in a process known as Trace Recording, and the output from several instruments was often recorded on one sheet so that the relative readings could be studies by the technical experts.

'Sheet' is a misleading term: the paper was often 50 or 60 feet long and four of us sweated over enormous baths to develop the image.

Special 16 mm cameras were also fitted to record the course of a test flight - these sometimes recorded external events as well as the cockpit, and were in black and white, or sometimes in colour. On one occasion I recall, there was a test with external view cameras of a flight in which rockets were carried in pods under the wings.

When the rockets were fired (they did not have live heads), there would bea plume of smoke, and on one occasion a pilot returned from his test flight claiming 'The bloody things were coming back at me!'. We fitted high speed 16mm colour cameras because no one believed him.

They showed that he was indeed telling the truth. The rockets were clearly seen bobbing about under and over the wings. Modifications were required! The plane was so fast that it was actually catching up with the rockets which it fired. I dare say things are different today.There were 14 or 15 people working in the photographic department at English Electric when I joined the company, though only about four were photographers. Two of these specialised in air to air photography and the other two were general photographers. I did none of the photography, but I did do developing and printing in the darkroom - someone there must have thought I was not yet ready to be let loose with a valuable camera! Those in use at the time were 5 x 4: both MPP and Linhoff. The person in charge of the photographic department once decided that the staff maybe needed some tuition in photography, and he arranged for the famous Walter Nurnberg - then a leading commercial photographer and of great renown - to come and show how to do it. He was a small, dapper man in his late 40's with glasses and when he arrived he had so little with him that we wondered whether or not he had come on his bicycle. (In fact he had been picked up from the railway station.) He had a very small suitcase and a tripod, and our session started with the photographing of some machinery in one of the hangers. His camera was a Rolleiflex, and his total equipment was a cable release and a hand held photoflood lamp which, with our help, was used to paint the machine with light.

When you consider that we had been photographing these machines on 5 x 4 cameras using many lights and big canvas backgrounds, we were not over-impressed and quite few of us wondered privately if it was not Mr. Nurnberg who needed the tuition from us. However, the results were quite good, though I doubt if we learned much from him. I understand that his charges for the day were phenomenal. From English Electric I moved to the firm of James Woolley Sons & Co Ltd in Manchester. Woolley's was wholesale manufacturing chemist with a large photographic department. I was taken on as a Photographic Sales Consultant to run an enquiry service. This was a best suit job! My suit cost 65 guineas from Andrew Vass (the most expensive tailor in Blackpool) and I thought 'Now I have arrived' ! The firm printed eight thousand copies (I still have about four thousand if anyone wants one!) of an attractive folded leaflet which had as its front page a representation of a Voigtlander Bessamatic - one of the great 35 mm cameras of the day - with a head and shoulders portrait of me holding a telephone in its lens. The camera was black and white but the lens was tinted yellow. The first inside page proclaimed Meet Mr. Hargreaves a man in a position to help you. There's little he doesn't know (Wow!), and the opposite page presented a full reveal of the lens picture, showing a rather younger and darker haired Roy Hargreaves than the present model, set against an array of enlargers, projectors and other photographic gear and chemicals, boldly entitled FOCUS ON OUR MAN - AT YOUR SERVICE. For two days after the service was launched the switchboard was jammed with calls seeking my expert advice, and remained jammed until Woolley's sorted out an extra dedicated line straight through to my desk.

Please Note:

There is more than one page for this Article.

You are currently on page 2

1st Published 01/12/1999

last update 09/12/2022 14:56:34

More Profiles Articles

There are 0 days to get ready for The Society of Photographers Convention and Trade Show at The Novotel London West, Hammersmith ...

which starts on Wednesday 15th January 2025